Edward Lively was born into poverty about 1545, and never quite got out of it. He was pursued by his creditors to the end of his days:

On one occasion, he returned home from a lecture attended by the queen to find all his goods impounded against payment of debts. . . . As the father of thirteen children, he could never get ahead of his bills. Ultimately he had to sell his large library 'for a pittance' to a covetous bishop, and from time to time found himself obliged to pawn other goods. 'My life,' he once said in a despondent mood, 'is nothing but a continual Flood of waters. After his wife died, he was completely overwhelmed,(1)

The scholar "took sick with an ague and a quinsy (2)," and died in four days; he was buried at St Edward's Cambridge, May 7th 1605. He was about sixty years old.

Training and Education

Lively was a scholar and later fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Trinity College, Cambridge.By his mid-20's in 1569 he had graduated; three years later he was awarded an MA. Continuing on with Hebrew studies he was taught by the reputed Oriental scholar John Drusius, a visiting Professor from Franeker, Belgium. Drusius had become an English fellow at Oxford to promote the study of Semitic languages in sixteenth-century England. Such was his fame as a Jewish scholar on the continent, that Drusius' Hebrew classes were frequented there by students from all the Protestant countries in Europe. He was highly skilled in both Hebrew and Jewish antiquities.

Lively was Regius Professor of Hebrew from 1575 to 1605. His published works include Latin expositions of some of the minor prophets, as well as a work on the chronology of Persian monarchs.

Ecclesiastical life

In 1602 Edward Lively received a prebend at Peterborough, and in 1604 he took a living in Purleigh. Only seven months after this he died.

Though he left eleven orphans without means of support, they survived and did well, and there are descendants of Edward Liveley living in the United States today.(3)

Scholarly pursuits

Lively's scholarship (was) exceptional for the age in which he lived. Classical learning, in which he himself was steeped, is recommended to all those aspiring to understand scripture. He stresses the contribution made by such non-Christian writers as Pliny, Horace, Homer, and Herodotus, to the understanding of the Bible: ‘For many parts of Scripture they are diligently to be sought unto, and not as some rash brains imagine, to be cast away as unprofitable in the Lord's schoolhouse; but especially for Daniel above all’ (A True Chronologie, 22). . . [I]n Lively's opinion these ‘profane writers’ were important sources for the illumination of the word of God.(4)

Lively's approach to translation blended three distinct sources in expounding the text: classical learning, the church fathers and post-biblical Jewish exegetes and historians. This is illustrated in two books he authored. The first was on five of the minor prophets in 1587, whilst the second was a commentary on the seventy weeks of Daniel 9: 24–27. The latter shows Lively's breadth of scholarship and of his attitude towards the Hebraic tradition of exegesis. His approach was to give a just account of the times as well as a true interpretation of the original.

Santiago de Compestela

flickr.com

If the commentator fails in either of these, ‘there is no hope to know what Daniel meant by his weeks’ (A True Chronologie, 27). In his search for the true interpretation he has constant recourse to the ‘judgment of cunning linguists and sound divines’ (ibid., 44). The result is that the comments of classical authors, church fathers, and Jewish exegetes are harnessed to the task of biblical interpretation. (4)

Dr Edward Pusey commended Lively as one of "the greatest of our Hebraists." Pusey himself had studied Oriental languages at Gottingen Germany and was Regius Professor of Hebrew at Christ Church, Oxford for half a century

Dr Edward Pusey.

Preparation for the KJV translation

According to McClure

He [Lively] was actively employed in the preliminary arrangements for the Translation, and appears to have stood high in the confidence of the King. Much dependence was placed on his surpassing skill in the oriental tongues. But his death, which took place in May, 1605, disappointed all such expectations; and is said to have considerably retarded the commencement of the work. Some say that his death was hastened by his too close attention to the necessary preliminaries. His stipend had been but small . . .

Edward Lively was appointed leader of the first Cambridge group. The team were commissioned to translate from 2 Chronicles to Song of Songs. His premature death after only a few months of translation work compelled Laurence Chadertonto fill the gap left by his passing.

Final commendation

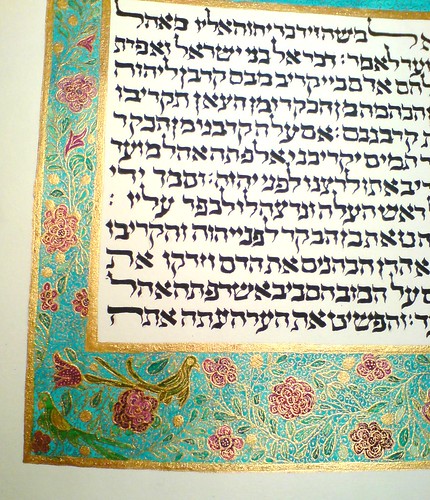

Illuminated Hebrew scriptIn the course of a distinguished career Lively proved to be a competent teacher and an able scholar. The letters which passed between James Ussher, later archbishop of Armagh, and his friends early in the seventeenth century testify to the respect in which he was held as a Hebraist by biblical scholars of his own day. His funeral oration, delivered by Thomas Playfere, Lady Margaret professor of divinity at Cambridge, demonstrates how successfully he had communicated his love of Semitics, and in particular his interest in and appreciation of rabbinic literature, to his contemporaries. (4)

Playfere shows the esteem in which the knowledge of Hebrew was held, when he says:

[The Hebrew tongue] ought to be preferred above all the rest. For it is the ancientest, the shortest, the plainest of all . . . [T]herefore . . unless he can understand handsomely well the Hebrew text, he is counted but a maimed, or as it were half a divine, especially in this learned age. (1.57) (4)

(1) Bobrick, Benson. (2001) The Making of the English Bible Lon: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p. 232

(2) Quinsy - an abscess in the tissue around a tonsil usually resulting from bacterial infection and often accompanied by pain and fever.

(3) Paine, Gustavus. (1959/1977)The men behind the King James version, MI: Baker p. 74

(4) G. Lloyd Jones. (2004) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography