Family and academic background

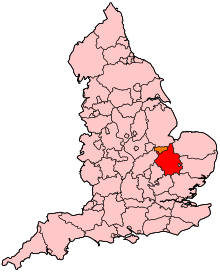

Thomas Bilson was born in 1546/7, was one of five children of German descent. The family were settled in Winchester for two generations, and had fairly close family links with the brewery trade, the local Council, Winchester College and Merton College, Oxford. Bilson was educated at the twin foundations of William de Wykeham, Winchester College (1559) and New College, Oxford, graduating BA (1566), and MA in 1570. He became a teacher in, and later Headmaster of Winchester College, 1572.

Winchester College Chapelcommons.wikimedia.org

Theological achievements

In 1579 Bilson resigned the headship of Winchester to concentrate on theological study, rapidly acquiring a BTh that same year, and a DTh two years later. He was elected warden of the college, as well as canon and prebend at the cathedral. In 1596 he became bishop of Worcester, and three years later bishop of Winchester. Bilson broadened his academic interests during these years and

now became ‘infinitely studious and industrious in Poetry, in Philosophy, in Physick, and lastly (which his genius chiefly call'd him to) in Divinity’ (Harington, 72–3).(1)Says McClure :

Anthony Wood proclaims him so “complete in divinity, so well skilled in languages, so read in the Fathers and Schoolmen, so judicious is making use of his readings, that at length he was found to be no longer a soldier, but a commander in chief in the spiritual warfare, especially when he became a bishop!"The bishop also enjoyed and wrote a little distinguished poetry, which may explain why he was chosen to bring the final touches to the Bible translation work toward the end.

Bilson’s writings

During these years he wrote well over half a million words in two books - The True Difference betweene Christian Subjection and Unchristian Rebellion(1585) and The Perpetual Governement of Christes Church (1593).

[These] established Bilson, alongside Richard Hooker, as the most scholarly and learned of a group of contemporary writers who used the joint challenge of papal supremacy and presbyterian democracy both to carve out a defence of the Church of England.(1)Bilson rejected both the right of the pope to depose a monarch or elect church ministers, and supported the political resistance of protestants on the continent. He believed the superiority of hereditary government depended for its validity on the original permission of the people, and that tyranny should be resisted in the face of arbitrary and unwise rule.

The harrowing of hell

Did Jesus descend into hell on our behalf, and endure our punishment, after He died? The phrase in the Apostles Creed might suggest He did. In a controversy which lasted from 1597 to 1604, Bilson interpreted the phrase literally, and this reflected the prevailing view of the time - whilst Puritans tended to prefer a metaphorical interpretation. Bilson maintained that Christ went to hell, not to suffer, but to wrest the keys of hell out of the Devil’s hands. Hugh Broughton, a noted Hebraist, aggressively opposed this, and his personal animosity towards some he disagreed with excluded him from the company of translators of the King James Bible.

Queen Elizabeth, in her ire, commanded Bilson, "neither to desert the doctrine, nor let the calling which he bore in the Church of God, be trampled under foot, by such unquiet refusers of truth and authority." [McClure]In response, Bilson wrote a treatise of half a million words, entitled The Survey of Christ’s Sufferings.faithvillage.com

Hampton Court Conference

Thomas Bilson preached at James I's coronation, July 1603. His Episcopal seniority made him one of the main combatants at the Hampton Court conference, January 1604. James had called the conference to give the Puritans an opportunity to speak their mind on then current and contentious ecclesiastical issues. But, Bilson didn’t want the conference to take place, as he felt the level and dignity of any discussion would be demeaned by their presence.

. . . according to Stephen Egerton [Bilson] had suggested to James that: “the Bishops (being esteemed the father and pillars of the Church, for gravitie, learninge & government, &c both at home and in forraine parts) might not be so disparaged as to conferre with men of so meane place and quality. (Shriver, 56)(1)During the conference Bancroft was highly combative whereas Bilson because of ill health, ‘stoode mute: and said little or nothing’ (Usher, 340).(1)

Bilson was now suffering from sciatica, arthritis, vertigo, ‘a continual singing in my head … many obstructions and extreme windiness’ (Salisbury MSS, 17.6).(1)Coronation chair - Westminster Abbey

flickr.com

Involvement in the KJB translation

Thomas Bilson was chosen, along with Richard Bancroft, as two of the most senior clergy, to review the entire draft translation of the Bible, and help put the final finishing touches to the all-important work. Once each company had completed its draft manuscript, and reviewed the drafts of each of the other five companies, Rule 10 of James 1 (as drawn up by Bancroft) required the entire work to be reviewed “by the chiefe persons of each company.” Rule 13 required that deans of both Westminster and Chester, and the Regius professors (RP) of both Universities be acknowledged as key participants, in the making of final textual choices. (2)

If any Company, upon ye review of ye books so sent, really doubt, or differ uppon any place, to send them word thereof, note the place, and withal send their reasons; to which if they consent not, the difference to be compounded at ye general meetinge, which is to be of the chiefe persons of each company, at ye ende of ye worke.If James’ absolutist claims were to be honoured, this rule would have been adjudged flouted, had it not been followed carefully. Hence, it is very strange if John Bois’ biographer is accurate when he says the committee was not composed of those who had been previously overseers or supervisors of the six companies, but that they started afresh. [Rule 10]

The General Committee of revision

The final committee must have contained up to twelve members. Directors present (and their associated ‘heavyweights’) would have included four or five Regius professors of Hebrew and Greek [John Harding (RP 1604), Andrew Byng (RP 1608), Andrew Downes (RP 1585), John Peryn (RP 1597), and John Harmer). Others were Lancelot Andrewes (Dean of Westminster), John Duport, John Bois, Thomas Ravis, and William Barlow (Dean of Chester).] We know from a surviving document of the notes that John Bois took during the proceedings, that this review committee for certain included John Bois, Andrew Downes, and John Harmar.(3) The other committee members are inferred from the need to strictly apply Rules 10 and 13 of the Royal commission.

Committee of review

The General Committee of Review met at Stationers' Hall, London in 1609. They received a list of readings of texts, words or phrases which were still in some doubt, even after the six companies had discussed them and failed to reach agreement as to the best rendering. Some of their final decisions would have been tentative. The Committee would have made known to Bilson and Smith the textual issues at stake, which needed their input. However, it is hard to believe that the final-final review restricted itself to a list of stated ambiguities. The two men could well have worked through sections of the entire Bible individually, looking for opportunities to improve both style and substance, if such were possible. Every word was theoretically open to challenge, especially with an ear to producing a pleasing, sonorous, lucid style:

So Bois put down word meanings as a dictionary would, or alternates as a thesaurus would; later still would come a choice among possible constructions for sound and rhythm and euphony of the whole. The Bois notes show how careful the translators were, first of all, to determine exact meanings or establish a permissable range of meaning. Final constructions thus appear, almost always, to simplify the Bois suggestions.(3)Stationer's Hall

flickr.com

The final-final review and revision

Miles Smith and Thomas Bilson undertook the final editing - already reviewed and revised - of the entire draft of the Bible. Bois’ notes show that the General committee not infrequently resolved a textual issue by recommending Andrew Downes’ preferences. The Bible itself shows that the two men probably had a definite say in some of the final choices. Just a few examples where the reviewers did not follow Andrew Downes’ choices (as perhaps initially recommended) are:

(1) 1 Cor 10:20 Downes: “And I would not have you partakers with the devil.” KJB: “and I would not that you should have fellowship with devils.”

(2) 1 Cor. 15:33 Downes. “Be not deceived; evil communications corrupt good natures/dispositions/manners/” The KJB final choice has “good manners.“

(3) 1 Thess. 5:23 Downes “. . . that your spirit may be kept perfect.” KJB: “your whole spirit . . . be preserved blameless.”

(4) 2 Tim. 2:5 Downes “and though a man labour for the best gain, try masteries . . . unless he strive and labour lustily.” KJB: “And if a man also strive for masteries, yet is he not crowned, except he strive lawfully.”

In the final editing the last learned men, Smith and Bilson, used the Bois words “perfecting holiness” in II Corinthians 7:1. In the next phrase they refused the Bois phrasing, “we have made a gain of no man,” in favour of “we have wronged no man.” For 8:4 they took the whole Downes reading, “that we would receive the gift, and take upon us the fellowship of the ministering to the saints.” (4)

However, the evidence suggests the procedure was a little more complex than making simple choices. The review committee probably left hanging some of the textual decisions needed, and offered possible alternatives. Then the manuscripts reached Bilson and Smith. It is highly probable the review committee suggested to Smith and Bilson their tentative resolutions of some knotty choices, in the hope of gaining the benefit of their viewpoint. However, Smith and Bilson would have found the tyranny of distance and competing duties hindered a proper resolution, in some or many cases. If so, in some cases they had simply to make their own choices, ignoring any referral to the General Committee. In other cases, they would have gone back and forth to the General Committee (either in session, or to various individual members within it) hoping to bring finality, whilst aiming to preserve harmonious relationships. It is not surprising if they were not entirely successful in this. Assuming there were some muted criticisms of supposed arbitrariness by one or two of the two reviewers, this would have emboldened Richard Bancroft, the overall manager of the project, and jealous of his perceived right to contribute to the final result, to make his own final changes!

Adding the finishing touches

Bilson was not required to add a prefatory address to King James, as this was Miles Smith’s privilege, and a brilliant essay he gave us. However, it is possible that Bilson helped Smith add the chapter headings. Bilson also wrote the dedication to the King placed in the front of the Bible, where “the glories of the Jacobean state are emblazoned here in unequivocal pomp and glory.” (3).

Final days

Thomas Bilson died in 1616, at a good old age, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. He was said to have been the exemplar prelate. His tomb celebrates the coming bodily resurrection - the ultimate hope of every true Christian, whatever his ecclesiastico-political views. The text on the tomb reads:

Here lies Thomas Bilson formerly bishop of Winchester and counsellor in sacred matters of his serene highness King James of Great Britain who when he had served God and the church for nineteen years in the bishopric laid aside mortality in certain hope of resurrection 18th June 1616 aged 69.

Other names associated with the Translation

There are five other names connected with the translation of the Bible, which have not been considered in these blogs celebrating the quadricentennial year of the publication of the King James Bible. They are George Ryves, Thomas Sparke, William Eyre, Arthur Lake, and Nicholas Love. These all may have had a hand in the discussions of the translators, whether formally or informally. John Bois mentions Arthur Lake in his notes, as one involved in the final review discussions in general committee. However, the source for Sparke and Eyre’s involvement is said to be undependable (4). George Ryves is referred to in a letter from Thomas Bilson to Sir Thomas Lake, which describes Ryves as “warden of New College in Oxford, and one of the overseers of that part of the New Testament that is being translated out of Greek.” Bilson also asked the King if Nicholas Love, schoolmaster of Winchester could exchange some livings with Ryves, so they could cooperate better in helping the work forward. Perhaps this work consisted in providing a path of smooth communication between the companies, thus spurring members on to see the work expedited.(4)

And so, four hundred years on, God has mightily blessed the amazing achievement of these fifty-two or more men. He continues to bless those who read and study it seriously; and He will go on doing so, as long as English is spoken and understood.

(1) Richardson, William (2004) Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

(2) McGrath, Alister (2002) In the beginning: the story of the King James Bible and how it changed a nation, a language and a culture. New York: Anchor Books, a Division of Random House, Inc. pp 174-175

(3) Nicolson, Adam. (2003) Power and glory: Jacobean England and the making of the King James Bible, Lon: Harper. p. 208, 217.

(4) Paine, Gustavus, (1959/1977) The men behind the King James version, MI: Bakerpp. 115-116, 116-118, p. 76, 72.

This is 52/52 index previous